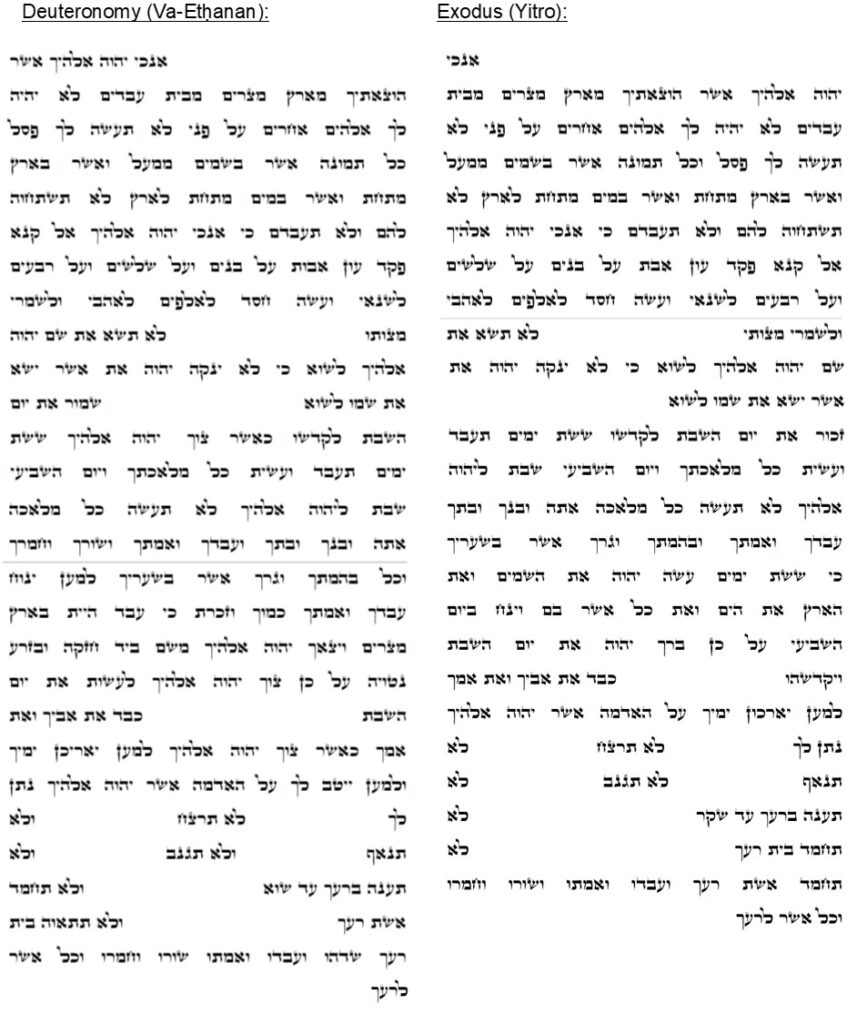

As appears in the Torah Scrolls:

The following image depicts the appearance of the Ten Commandments in Torah. As one can notice even without reading the text, the Deuteronomy version seems to be longer, with more words in it. Let’s dive in, and examine the differences section by section.

What Is a Commandment? What does the Hebrew word “Dibrah” mean?

In Hebrew, words are conjugations of mostly three letters combination. Each conjugation means something different: however, most of the time the meanings relate to each other. The words Deuteronomy, commandment, word, desert, speak (v), a thing, are all coming from the same root:

What is the First Commandment?

The first topic of discussion is: what is the first commandment? Here is what are our sages say about the issue.

Rashbi (Rabbi Shim-on Bar Yoḥay, 2nd Century CE) supports the same argument, and refers to Leviticus 18:2:

Speak to the Children of Israel saying I am Adonai your God.

דַּבֵּר֙ אֶל־בְּנֵ֣י יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל וְאָמַרְתָּ֖ אֲלֵהֶ֑ם אֲנִ֖י יְהוָ֥ה אֱלֹהֵיכֶֽם׃

This verse uses the same phrase and is certainly not a commandment there. Rashbi uses G’zera Shavah method (drawing an analogy from one case to another, verbally identical) to prove his argument.

Rabbi Shim-on Kayarrah, the author of the codex “the big Law book – Halakhot Gedolot”, lived in Basra (Babylon) around 700-800CE. In his work he tried, probably for the first time, to enumerate all the 613 commandments given in Torah. He considered as commandments only those who have behavioral characteristic: “do this, don’t do that”, ignoring statements relating to faith. As a result of that decision, he concluded that the first verse was not a commandment.

Rabbi Yehudah Halevi [1075-1141] also believes, as it may be understood from his book “The Kuzari” that God is not just a metaphysical entity. He IS the Source of Majestic Power and creator of all universe. And He is also the particular One that delivered the Israelites from Egypt and turned them into a Nation. He us the One that is mentioned in the first Verse of the Ten Commandments. Hence, it seems that in his opinion, that very first verse is not a Commandment.

The Maimonides [1138-1204] (Rambam – Rabbi Moshe Ben Maimon) takes this simply as the first positive Mitzvah. In the introduction to the Mishne Torah, his big codex of Jewish Law (contains 14 volumes in addition to the Introduction), the very first Positive Commandment is:

The first Commandment of the Positive Mitzvot is to know that the Lord God exists. As it is said in Ex. 20.2 and Deuteronomy 5:6: ‘I the LORD am your God’.

מִצְוָה רִאשׁוֹנָה מִמִּצְווֹת עֲשֵׂה, לֵידַע שֶׁיֵּשׁ שָׁם אֱלוֹהַּ, שֶׁנֶּאֱמָר: “אָנֹכִי ה’ אֱלֹהֶיךָ” (שמות כ ב, דברים ה ו)

The Nachmanides [1194-1270] (Ramban – Rabbi Moshe Ben Naḥman) – explains the position of Ba’al Halakhot Gedolot. He uses a parable from the Meḥilta D’Rabbi Yishma-el (20:3) as a proof to his thought:

“There shall not be unto you any other gods before My presence”: What is the intent of this? An analogy: A king of flesh and blood enters a province and his servants say to him: Make decrees for them. He: When they accept my rule, I will make decrees for them. For if they do not accept my rule, they will not accept my decrees. Thus, did the Lord say to Israel: “I am the Lord your G d. There shall not be unto you, etc.”: Am I He whose rule you have accepted? They: Yes. He: Just as you have accepted My rule, accept My decrees — There shall not be unto you any other gods before My presence.”

According to Ramban, the People of Israel already accepted and believed in the Sovereignty of HaShem in Egypt (Exodus 4:30-31). “Aaron repeated the words that Adonai spoke to Moshe, and performed the signs in the sight of the people. Hearing that Adonai noticed their sufferings, the People of Israel believed in God, they bowed and prostrated low in homage.” Accordingly, the opening statement of the Covenant is a reminder to that belief.

Moving forward 1000 years, Rabbi Jonathan Sacks adds another element to the discussion that helps him form his own opinion:

“Thanks to the archeological discoveries about which I wrote in the previous Covenant and Conversation, we now know that the biblical covenant has the same literary structure as ancient near eastern political treaties. These treaties usually follow a six-part pattern, of which the first three elements were [1] the preamble, identifying the initiator of the treaty, [2] a historical review, summarizing the past relationship between the parties, and [3] the stipulations, namely the terms and conditions of the covenant.

Seen in this context, the first verse of the Ten Commandments is a highly abridged form of [1] and [2]. “I am the Lord your God” is the preamble. “Who brought you out of Egypt, out of the land of slavery” is the historical review. The verses that follow are the stipulations, or as we would call them, the commands. If so, then the Halakhot Gedolot as understood by Nahmanides was correct in seeing the verse as an introduction to the commands, not a command in its own right.”

The beauty of Judaism is that we can have this argument going on over a time span of millennia. It is as if all participants are sitting together with us in this room and the conversation goes on. There is no one “correct” or “false” answer. The truth is the dialog and the discussion itself.

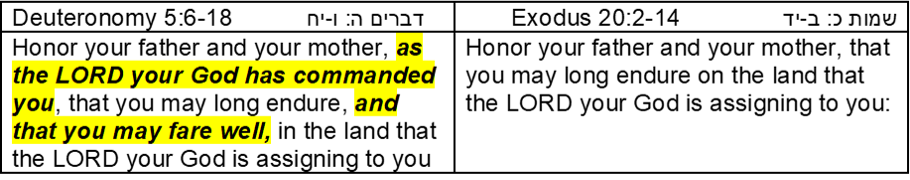

The Forth Commandment, Word: Honor your Parents

Why the addition of “as the LORD your God has commanded you” and “And that you may fare well”?

in my humble opinion, both additions re-emphasize the idea that we discussed earlier. The first addition, is a pre-amble that follows the then known format of treaties, as explained by Rabbi Sacks. As for the second addition, it comes to mitigate the question why should one follow this Word. We, Jews, ask these kinds of questions: “What good is in living long, but miserable life full of suffering?”. In that case, we say, Moyḥel Toyves (in Yiddish – thank you for your kindness, but no thanks…). The addition solves the conflict by stipulating that if one fulfills this Word, the long life will be good life.

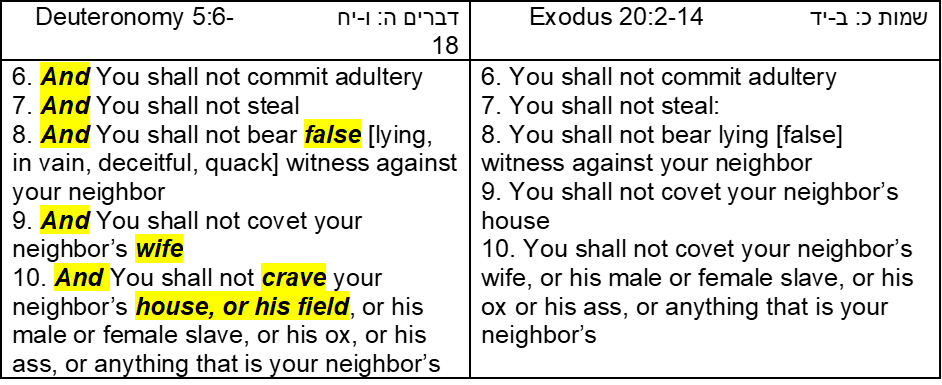

Words 6 through 10

In the Deuteronomy version, the Words 6 through 10 have the added AND prefacing the You shall not… Why? Probably to make sure that no one interprets this list as an ‘or’ list but rather an ‘and’ list. One MUST follow all of these, no exceptions.

Note the difference in Word 8: Exodus version is talking about עד שקר – can be literally translated as “a Lying Witness”. Many translations use “false witness”, which is in my opinion, is too mild. Deuteronomy version is calling out עד שווא – closer to a false witness and also a witness that provides irrelevant, confusing, null, in-vain testimony, that may be true, but is misleading and doesn’t help the case in hand.

The word תַּעֲנֶה – Ta’aneh that appears in both versions means you will answer (a question) and in biblical Hebrew, testify. Conjugating the root of this verb (ע.נ.ה.) in a different Building means to torture. The audible difference in the future tense between the two is miniscule, and can hardly be noticed. Certainly, such a witness tortures both the accused and the court.

Look at the differences in the language of Words 9 and 10 in the two versions: what do you see?

Exodus Word 9 talks about the House of your fellow human being while Deuteronomy talks only about the Wife. Both versions use the same verb – covet. Exodus Words 9 and 10 use the same verb, covet (תַּחֲמֹד), hence combining both to a single Word makes sense. Exodus Word 10 counts the Wife with the rest of one’s [male] possessions, turning her into an object, a possession.

Deuteronomy’s Word 9 talks only about the Wife of the fellow human, using the same verb as in Exodus, covet. The meaning of that word has sexual connotation: the root implies to nice looking and pleasant character. Word 10 list the house and all other possessions, in a similar way to Exodus less the wife. However, the verb is different – תִּתְאַוֶה – more like desire, wish for (something more tangible, materialistic).

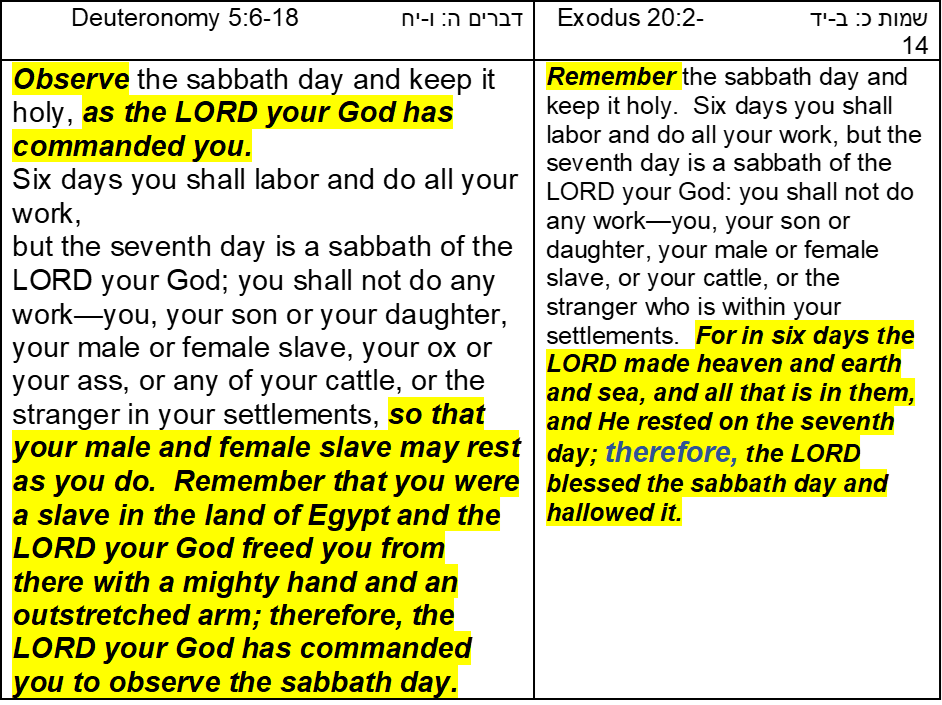

The Third Commandment, Word: Shabbat

The very first word is different: זכור – Remember in the Exodus version, Vs. שמור – Observe, guard, in the Deuteronomy version.

Talmud Bavli (Sh’vu-ot 20b:9) teaches us: like that which is taught in a baraita: “Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy” (Exodus 20:8), and: “Observe the Sabbath day, to keep it holy” (Deuteronomy 5:12), were spoken in one utterance, in a manner that the human mouth cannot say and that the human ear cannot hear.

We sing the notion of this idea in the first four words of the Lekha Dodi – “Shamor VeZaḥor B’dibur Eḥad”

By the way, this argument also explains the differences in Word 8 between the lying and false witness. According to Midrash, both words were said in one utterance that Moshe heard and understood. He then translated it into two different verbs so the People can follow the full meaning of the Word.

The first version is talking about the Zaḥor – remember. One only can remember things that happened in the past, whether one witnessed or heard about them. At this point in time, all that The Israelites have – memory. They still do not have the experience of observing Mitzvot. “For in six days Adonai made heaven, earth, the sea and all that is in them, and rested on the seventh day. Therefore, the LORD blessed the Sabbath day and hallowed it.”

This commandment inspires us to strengthen our faith in the uniqueness and oneness of Hashem, the One Creator of Universe. By observing the Shabbat as a day of rest, we remind ourselves on a weekly of His stature. We get closer to God by emulating an attribute that He demonstrated. After creating the Universe, He rested, ceased of all creative activities and rejuvenated the soul (וָיִנָפַשׁ) on the seventh day. This notion actually supports the Rambam’s assertion that Faith in God’s existence and Emulating God actions is a positive Commandment.

The form of the verb is infinitive (Zaḥor and not Z’ḥor) rather than imperative (as should be in a Commandment). Rashi comments on the use of the infinitive mode of the word Zaḥor. He said that the memory of the Sabbath day must be first and constant in the mind of the Israelites. Not only on Shabbat, but also must be in one’s mind during the six days of the work week. That is why the Hebrew names of the days are: First Day (after Shabbat) – Sunday; Second Day (after Shabbat) – Monday; and so forth until Friday – Sixth Day (after Shabbat).

Commentators also connect the two different verbs to Positive and Negative Commandments. A Positive Commandment is “Do this” while the Negative Commandment is “Don’t dare doing that”. By comparing the use of Zaḥor to other instances with similar context they claim that it relates to Positive Commandments. Similarly, the Shamor, on the other hand, is connected to the Negative Commandments. Thus, one who keeps the Shabbat is considered as if he/she has kept all 613 Commandments.

The reason given to Observe the Shabbat in Deuteronomy is social. All living that God created are equal to each other and to oneself. So, on Shabbat, one should do no work, but rest; and so should every living creature as one does. And the reason here is a memory, a relatively fresh one. Moshe just refreshed that memory to the People of Israel: Because you were slave in Egypt.

The Deuteronomy version uses the Remember Verb and the Observe Verb: Observe the Shabbat and Remember that you were slaves in the land of Egypt. By keeping Shabbat – one will merit as one keeps all 613 Mitzvot.

Going back to the very beginning, to the discussion about what is the Commandment. The appearance of “as the LORD your God has commanded you” in this Word (in Deuteronomy) supports the position of Rabbis Yehuda Halevi, Shim’on Kayarrah, the Nachmanides, and Jonathan Sacks regarding the First Word that actually starts with “You shall have no other gods beside Me”.

The videoclip of the conversation and the Shiur (lesson) can be found here, it is about 1 hour and 11 minutes long. I dedicated the study to the memory of two of my prominent teachers. My father, Rabbi Arie, that passed away on the 10th of Elul, 45 years ago and also would have his 120th birthday a few weeks later. The second is Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, that in a miraculous way, bears in his name the names of my ancestors on both the paternal and maternal sides. What a blessing!

PS: This essay provoked an interesting Conversation with D., a young friend of mine with an amazing soul. He questioned the meaning of some of the Ten Commandments, and brought to the discussion his personal experience. He then continued to develop universal doubts, and philosophical thoughts about good and bad.