Introduction

A person’s character and behavior are a result of very many elements. Among them, one can list the environment in which the person grew up and is living, one’s family and their history, education, and events that one goes through during a life. It takes reflection and hindsight to recognize what were those elements and how each contributes to building a person’s character.

The health challenges I struggled with also presented the opportunity to look back at my life and uphold seminal moments. Many of you, friends, inspired me to share some of the events that shaped me. My stories of Mom surviving the Holocaust, the High School Experience and fighting Cancer are already available on my website. I will most likely add more in the future. I hope that by sharing some of my own experiences, they may inspire even a single person to better face one’s own challenges.

In essence, the tale I share here speaks to the spirit of the IDF (Israel Defense Forces) and the Defense Industry; and those of us who were honored to serve in both. It is about resilience, perseverance, creativity and living with the unknowns. As I reflect, I can see clearly it reinforced my drive to serve something that is bigger than me. Something much more important than putting bread on the table. This motivation and demeanor of operation is valid for me and for so many Israelis, and prevails even today.

This story is almost 40 years old and that is why I feel that I can tell it now. Yet, I will use initials for most of the names and disguise some other details.

The Israeli Navy always pursued to modernize its Gal (wave, in Hebrew) Class submarines with better systems. The purpose of “K’arat Dagim” project (“Fish Bowl”) was to equip the submarines with a new, advanced, Search Periscope. Let me, the cook, tell the story how this Fish Bowl was prepared.

After my service as an officer in the Israeli Navy, I joined Rafael, an arm of the Ministry of Defense. Rafael in Hebrew was the acronym that meant “Armament Development Authority”. As an engineer in the Electro-Optics Research Department, I participated in the development of a particular night vision FLIR system.

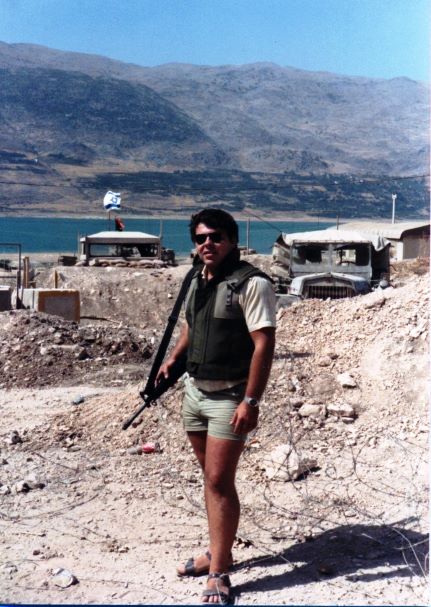

This system mapped minute temperature differences that exist in nature to a real-time video image. This thermal imaging technology is effective regardless of the ambient light that exists even at night.Our State-of-the-Art system was packaged in a 15” by 10” square box and weighed about 30 pounds. We tried it out together with the IDF Ground Forces in various operational scenarios, taking me even to Lebanon… But that belongs to yet another story…

The birth of the solution – feasibility study

The story starts somewhere during 1985. My boss called me into his office and handed me a couple of blueprints. I knew, right away, that they were not a product of the Holy Land: our blueprints were actually brown… He stated, “these drawings depict the free volume in the periscope that Kollmorgen builds for the Israeli Navy Gal Submarines. Can you please fit our FLIR into the volume defined in these drawings?”

I still served in the Navy as a Reservist and had some connections. I learned that the US Administration adamantly denied our request to incorporate a FLIR system in the new Periscope. A probable reason for the American rejection was that this strategic capability was an integral part of the Nuclear Submarines. Another reason might be that the system the Americans used was large and couldn’t fit in the IN’s Periscope. So, the Israeli Navy insisted that Kollmorgen will subcontract us, Rafael, to provide the Thermal Imaging System.

I encountered this phenomenon before, and faced it again, many times later. We had to develop ourselves the means necessary for our own defense. Means that were available to other nations that refused to provide those to Israel. We, Israelis, bear the ultimate responsibility to ensure that “Never Again” will prevail.

It took me a few minutes to get my bearings and convert the dimensions on the drawings to mm. Darkness fell on my eyes. The outside diameter of the periscope was 4” (10 cm) but the inner diameter that I could use was smaller. Some of the “real estate” in the inner volume was dedicated to other functions: direct optical channel, communications and cables. The only “space” that was left to potentially fit our FLIR was about half of the Periscope’s internal diameter. I quenched the urge to return to my boss and tell him my honest opinion about the feasibility of this idea. At minimum, I owed him (and myself) the justification of my learned opinion with a few drawings…

I spent the next two weeks in my room, in front of the old-fashioned drafting board. At that time, we at Rafael, only dreamt about Computer Aided Design (CAD) systems.

The Department was developing then a new, smaller and better in performance, detector then we used in our FLIR systems. I assumed that it would be ready whenever I’ll need it, and used it as my basic building block. The cryogenic cooler I needed to use (a requirement for FLIR systems) took half of the volume available to me. And I still had to allocate room for electronics, scanner, optics… I worked on several options, even tried a shoehorn to squeeze all in; but all of those options failed. At least I had sketches of 5 different “No-Go” options to show my boss that it’s not going to work.

When I presented my work, the first sentence I told my boss was in English: “NO WAY our FLIR will fit in the allocated volume.” I then took a breath, and prepared to show him the fruits of my efforts. But before I could commence, my boss asked me with a quiet, smiling voice: “Which way, did you say?”

I got it. The term “impossible” does not exist in the vocabulary of Rafael. Just as it was not there during my Officers’ training nor during my service in the Navy.

Back to the drafting board, with a new sheet on it! I started thinking creatively, in a non-linear way. Rather than letting the optical designers have free hand to allocate lenses, I dictated where they will be. Working with the electronic wizards we minimized the amount of electronics needed next to the detector. Just as my boss didn’t take “no” for an answer, I now I had no mercy for the mechanical designers. They will have to be very creative in their solutions too. Somehow, on paper, it all seemed to fit. Clearances were only fractions of mm, and yet, it was feasible. Proudly, I showed my solution to the boss. “Nice,” he said, “that is certainly one of many ways to solve this problem.” He then added, just before I left this office, “I knew that you would find the way.”

Pre-award activities

The next few months entailed hard work on details, covering all aspects of the program. Kollmorgen presented us with the relevant requirements that the Israeli Navy had specified in their request for the Periscope. In response we developed the detailed technical specifications for Kollmorgen, that if fulfilled, will comply with the Navy’s requirements. Alas, the program was classified as “Secret” and so were the documents we generated. Once our documents got to Kollmorgen, they became “US Secret.”

Kollmorgen could not share, nor discuss, these documents with us, the foreigners. We each held our own documents close to our chest as we talked to ourselves about elements within a document. Both Kollmorgen and Rafael teams, talked loud enough, making sure that the other party could hear. It took time for the security organizations on both sides of the ocean to resolve this issue. Once we received the clearances, we could work together more comfortably

The time came to meet the “Customer”, and I became petrified with fear. I was a young, relatively inexperienced, Mechanical Engineer. My knowledge in optics, electro-optics, Infrared physics, electronics, software, reliability and so many other disciplines was extremely limited. In my fear, I asked the advice of the head of our department, Dr. K.

He heard me out, calmed me and told me two things. “First, you are correct in your assessment. However, you know the system that you lead and its design better than many others. I am certain that you know it much better than your American counterparts. They don’t know all the details and design considerations that you went through on your way to the solution.” He then added the second pint: “There is no shame in responding with ‘I do not have the answer to your concern. Please, let me get back to you with an answer tomorrow’.” Dr. K then assured me: “I’m here, call me with any question you have, and I will make sure you will have an answer the following day”.

Indeed, Dr. K was correct. During the meetings, I was able to answer most of the questions. For some, I provided answers the following day, after receiving the results of additional calculations from my colleagues at Rafael. I learned another lesson about Rafael’s organizational behavior and DNA. Anyone that represents Rafael in front of a “customer” or “a user,” is akin to the warrior on the frontline. Supporting that warrior is the highest priority to all who are back in the office. The guys back at the office dropped everything when I had a question. They immediately mobilized to generate the answer for me. That lesson accompanied me throughout my professional life, both as the recipient and the provider of that support.

This phase came to a conclusion with a handsome order from Kollmorgen. For the amount of over $2M (at that time this was a considerable sum), we committed to supply 6 systems within 4 years from this contract award.

After The Award – Running the Program

Shortly after I returned from the US with the signed contract, the Head of the Division, summoned me to his office. He appointed me to lead the program and added a very clear instruction: “Together with this appointment I deposit more than $2m in your account. I expect you to handle it with the same fiduciary responsibility as if it was your own private account.” I responded: “Aye Aye, Sir”, “I can, and will do that.”

There were so many technical challenges to overcome, some of which we had no idea how to tackle. I will not elaborate on the technical aspects of the project, but rather focus on some anecdotes that accompanied us. Yet, it is a technical program, and without some technical stories one can miss its whole essence.

A Few Stories About the Optical Design

The design of the optical system was quite a challenge, because it involved split responsibilities between Rafael and Kollmorgen. The optical channel included a folding mirror that provided the ability to change the elevation of the line of sight. In front of that mirror, was a lens, that needed to move in conjunction with that mirror. We did the design, and Kollmorgen provided the dynamic positioning of both the mirror and the front lens. We had no way to ascertain if Kollmorgen met our requirements. If they failed, our system won’t meet the specification requirements. Behind the scenes I educated my friends in the Navy what to look for and which questions to ask. We both did our best to make sure that Kollmorgen did a good job on that piece.

The Dome that sealed the interior of the Periscope and served as the FLIR’s window posed another challenge. Our attempts to subcontract the Dome’s coating to American companies were in vain. No American company received the required license to export that technology to Israel. We had no choice but to develop our own. Then a new issue arose: how do we verify that the coating withstands the extended exposure to sea water?

We immersed a few coated disks in sea water for two years, and tested them monthly. This required someone to drive monthly to Haifa Port and collect slimy seawater to continue the test for another month. We showed that there was no degradation in the performance of the coating and Kollmorgen approved it.

My counterparts at Kollmorgen

The Project Manager at Kollmorgen was an Israeli physicist. He graduated the Technion and left Israel for the US after his military service. That fact didn’t make our lives any easier. There were no special discounts because of this “special relationship” one Israeli to another. It also limited our ability to converse among ourselves in Hebrew, as he understood everything! He also foresaw all the tricks and manipulations we tried to pull and was able to circumvent them all. In retrospect, though, he understood the importance of the project to the defense of Israel. He made considerable efforts to squeeze the last drop of performance from the system and make the program a success.

My primary point of contact was the Contract Manager, Ms. Connie Goonin. Every communication had to go through her, both from Kollmorgen to Rafael and vice versa. Ms. Goonin held us all in check, and made sure that everything was well documented. Yet, another lesson to learn, that didn’t bode well with us Israelis. We tend to pay less attention to these elements of “well documentation” in the life of a program, considering that aspect less important. Israeli’s use “trust me, it’s all going to be fine” statements much more than the American culture can tolerate. This very same Connie, became my spouse 15 years later, but that belongs to yet another tale – a fairy tale.

Traveling Abroad

During the program we had to meet many times Kollmorgen, some of the meetings were in the US. For each and every such trip I had to submit a detailed travel plan to a committee for approval. In the 80’s, a 3-day round-trip would cost much more than the same trip over a 5-day period.

One trip was for an interim design review, which would take 3 days. After I compared all the costs involved 3-days vs 5-days, it so happened the 5-days option was less expensive by $500. The plan I submitted showed a longer stay abroad for 5 days, with meetings over 3 days, for less money. The chairman of the approval committee demanded that I shorten the trip to 4 days. I explained to him that with my plan I save the program $500! The guy didn’t budge: “I don’t care about savings, it’s not my money.”

Still furious, I called the head of the division: “I cannot guard ‘my bank account this way!’” The division head spoke to Rafael’s CEO who, in turn, approved the travel plan, regardless of the decision of the committee. Upon my return from the trip, the division head called me to his office. He praised my attitude and financial prudence, and made a request: “Next time, please write in your travel plan 5 days for meetings, regardless of how long it takes.”

I understood; sometimes, it is better to be smart than right, especially when your boss’s boss asks you to.

Controlling the Cryogenic Cooler

We had to provide Kollmorgen with the FLIR’s Cryogenic Cooler power supply that they would later integrate into their system. They were responsible to implement the logic that controlled the operation of the Cooler. As we progressed it became clear that this division of work did not make sense. Kollmorgen offered to add the Periscope Power Supply Unit to our deliverables, for a nice increase in the program’s price.

Excitedly, I looked for “volunteers” to take the easy job. There were really no technical challenges, just re-package a few “off-the-shelf” subunits. The responses I received were: “Design and build a power supply? …Nah… not interested, regardless of the profit.” I realized money, profit and loss, did not interest the researchers of Rafael, a branch of the Ministry of Defense. Disappointed, I declined the offer made by Kollmorgen. They decided to remove the cooler’s power supply from our deliverables and reduce the contract value by $100,000. They still had to control that cooler, because it was a part of their workshare.

The electronics engineer of the project, presented me with a brilliant solution how to control the cooler. It involved an additional resistor, capacitor and an electronic gate to one of our electronic boards. The total cost impact of the solution would be less than the cost of a McDonald’s Big Mac meal. Kollmorgen wasn’t making progress with the cooler logic; thus, the timing was ripe for me to offer a swap. I met with the CEO of Kollmorgen division that built the periscope and offered to relieve them from that burden.

I offered a deal: Rafael will assume responsibility to control the cooler, and Kollmorgen will keep the initial contract price. His attempts to convince me to reveal the solution went in vain. “Let’s agree on the principles, and then I will convince you that we can do it,” I insisted. After reaching an agreement, I pulled out a piece of paper with the schematics our engineer had prepared for me. It was so simple that even I, the mechanical engineer, could explain it flawlessly.

The explanation convinced the CEO of the division and his electronics engineer that the solution worked, but he was furious. “All this costs less than $100, and you want $100,000 for it? Are you out of your mind?” he demanded.

Calmly, I responded: “let me please tell you a story… hopefully it will convince you”. I told him about the expert that was called to help with the dynamic balancing of a huge steam turbine. The management of the powerplant called that worldly renown expert after all the local wizards failed to do the task. The expert came, checked the turbine, turned it left and right, and then stopped it at a certain point. He opened his briefcase and pulled a little hammer out of it. Aiming it very carefully, he hit the turbine at a spot with his hammer. Lo and behold! The turbine was now perfectly balanced. The invoice came shortly after, with one line: $50,000.

The CEO of the powerplant was perplexed. $50,000 for just a small hit with a hammer? Impossible! Yet, being polite, he asked his aid to request a breakdown of the costs from that expert. The response was not too late to arrive: “cost of hammer – $5. Cost of knowledge, how, and where to use it – $49,995”.

The Division CEO of Kollmorgen laughed, as he understood the message. It could have cost him much more to try and solve the problem himself. We shook hands, again, as the CEO instructed Connie to update the contract according to our agreement.

Our history told us, again and again, that we cannot lose even a single war. The Motto of the Mossad, verse 11:14 in Proverbs, is engrained in many of us, Israelis. It says: “For lack of strategy and stratagems a nation falls, and deliverance comes with much planning and many counselors”. That was – and is – true for me too. Not that I felt that we were at war with Kollmorgen; yet, we had our disagreements. Loosing this one could hurt us financially and lessen our ability to do more for the defense of Israel.

Critical Design Review – CDR

The Critical Design Review (CDR) is a major milestone in any program and so it was for us. We had to present the complete design of the system to the smallest detail to Kollmorgen and the Israeli Navy. They would ask questions about how the design meets all the requirements, and what are the risks in it. We will explain our risk mitigation strategies, our readiness for production, and respond to questions on many other subjects. It was also a major payment milestone in our program: success in the CDR granted us a $1/2M check!

Our team included A, (Systems and Electronics Engineer), N (Physicist and Optical Designer), Y (Lead Mechanical Engineer) and your humble servant. We left Israel on a Saturday night, carrying with us loads of documents, drawings reports and transparencies. Anything we thought would be necessary to answer any foreseeable question that may arise during the CDR. We planned for CDR to last the whole week, so our return tickets were for the following Saturday.

Monday, 8:00am. We all convene in the largest conference room at Kollmorgen. The four of us face a sizeable battery of American engineers and managers. The Israeli Navy is also present, with Lieutenant Commander A (Head of the IN’s Optronic Branch) and Major Y. We all ate sandwiches for lunch in parallel to continuing the discussions. Dinner was, again, sandwiches that we consume during the meeting. The day adjourned around 9:00pm.

Tuesday was an exception: we left for a dinner in a restaurant at 8:00pm.

Wednesday Thursday and Friday followed the same pattern as Monday. We explained the drawings and answered questions about materials, tolerances, logic design, heat dissipation concerns, to name a few. Performance, electromagnetic compatibility, reliability and failure modes analyses were scrutinized by Kollmorgen and the Navy experts. Schedule, delays we experienced on certain elements and how we mitigated those delays were yet another subject to talk about. Everything was looked at with a high-power magnifying glass, no stone was left unturned.

Friday night, the last day of the CDR. It’s already 10pm when we finish to go over the last slide, and no further questions are asked. Z, the Program Manager, asked us to leave the conference room and wait outside. They needed to determine if we met all the requirements for the CDR and whether it was a successful review. Little after midnight, he called us back to the conference room. On the whiteboard they made a list of the subjects we discussed during the CDR. Next to each item they listed their expectations, and the specifics in which we fell short in meeting them. Z went over the matrix and summarized the impression from the CDR. “All in all, it was a successful review,” he said, “however, we cannot approve its completion. We will do so after you will complete the shortcomings that I presented to you”.

“Sure, I understand,” was my response, as I continued: “my apologies for not explaining our design well enough. Why won’t we clarify some of these points now?” I didn’t wait for a response, and rather called up A. “A, can you please clarify these misunderstandings in System Engineering and electronics design?” A came up to the front of the room with his book of slides and elaborated on the open questions. Then came the turn of N, who explained issues in the performance analyses, and Y then answered mechanical design concerns. I was the last to come up and respond to the additional questions that were still open.

During this session, I had one image that guided me. It was in the biography of the IDF’s Chief of Staff from a decade earlier, Raful (Rafael Eitan). He described the battle for the San Simon Monastery, in which he was wounded. He said in his memoir: “when it rains in the battlefield it also rains on your enemy”. We were tired, and wanted to return to the hotel for a short nap before leaving for the airport. The Kollmorgen guys and the Navy officers were also tired, and wanted to go back home and start their weekend. The question then was, who will hold out longer, or who will blink first?

It was close to 5am on Saturday morning, 21 hours in the conference room, when Z interrupted my presentation. “Let’s take a short break. Emanuel, can you please come with me to my office?” I followed him. In about two hours from then, I thought, we needed to leave for the airport. Z closed the door behind me. We only allowed ourselves to talk in Hebrew when we were alone, behind closed doors. “Here is your Certificate of Milestone Accomplishment”, he said in Hebrew, “take it and get the hell out of here!” I agreed with his request to send him the supplemental information we presented in the last 4 hours within a week of our return home. We packed our stuff in minutes and left for a couple hours nap, before heading to New York.

Epilog

We delivered the first systems in 1989, pretty much according to the original schedule. It so happened the Kollmorgen had longer delays in their program execution, so the Israeli Navy couldn’t blame us for it. This was the first project that was designed in its entirety on the new 3-dimentional CAD system that Rafael procured. Indeed, as a result of that we had very little to rework, as everything fit in place very smoothly. The project developed many additional technical breakthroughs that served in other projects at Rafael decades later.

The project was also very well appreciated by the Israeli Navy. The periscopes with our thermal imaging systems were migrated to the next generation Dolphin Submarines, after the Gal submarines retired.

The “Never Again”, ensuring that our People will never experience what my mom went through during the holocaust, motivated me. Viewing obstacles as opportunities and facing the unknowns with creativity, optimism and resilience contributed to the success of the program. This experience strengthened within me the qualities that I already gained during my time in K’tziney Yam High School. It added and strengthened my determination, resilience, out-of-the-box thinking and the ability to operate under uncertain conditions. Making decisions based on sketchy and partial information became almost a way of life for me. Along with that came excessive self-confidence that got me into trouble later, but just enough to regain some humility in later years.