Prolog

My father was 53 years old when I was born, and naturally he passed away when I was young, only 22 years old. He had gone a lot through his life: he lost his first wife, the mother of his two sons and daughter when my sister was only 2 years old; his two sons fell during and after the war of Israel’s Independence. For me, he was an educator, director, mentor and disciplinarian rather than a dad. I assumed that it is more than likely that his demeanor was a result if his life experience, much of it is still unknown to me.

My mother was a holocaust survivor and 19 years younger than my father. She was sometimes distant, something like the “lights are off”. Yes, she tried, sometimes successfully, to mask it with laughter and jokes, but deep inside, I felt and knew that it is only a mask. She wasn’t the hugging and kissing type of a mother. She was the busy bee worker type that made sure that everything is in order. The house was clean, our cloths were neat, ready for us to wear. Most importantly, there was food on the table regardless the scarcity we experienced some times. And stashes of supplies for “just in case” situations. Throughout my mother’s life she refused to ever talk about her experience during the Holocaust. For years, I asked her repeatedly to tell me her story; every time she shook her head and walk away.

It happened during one of my visits with her at the assisted care facility she lived in. I think that it was only a few months before she passed away. Mom, on her own accord, said a few sentences, three in total, about her holocaust experience. It sounded like listening to a news item, reported by an investigator completely detached from the situation. There was no show of emotion, no personal description of the feelings accompanying the experience, nothing. There was just a hollow dispassion.

I choked. I hardly swallowed, holding my emotions in check. As I closed her room’s door behind me, I couldn’t hold it any more. Tears rolled freely as I sobbed in reaction to what I heard. What did I expect from Mom? How dare I hold complaints and point fingers at her behavior? It is an absolute pure miracle that I am.

I couldn’t even start to comprehend the full meaning of her experience and its ramifications. There were so many missing details in her story, that prevented me from understanding what it meant for me.

Years after she passed away, I started inquiring how to find more information about her experience. Unfortunately, there was basically no one to ask. All the relatives – brothers, sisters, friends, and in-laws – had already passed away. In my research, I found out that there is an archive in Germany that held details of survivors. Yes, they had information about Mom and they sent it to me. A German speaking friend helped me understand what was there. Nothing of any significance about what she went through; it was all about a claim for compensation that was declined.

The State of Israel recognized Mom as a victim of the Nazi atrocities, and paid her a modest monthly fee. I called the relevant government agency and found that they did have a file on Mom in their archives. They even pull it out for me and let me read, take notes and make copies of relevant pages. The most riveting document there was her own testimony to the investigators of the Bureau that handled these cases. Here it is, as much as possible with her own words, as if she were here to tell her story.

Testimonial.

I, Naomi Ben-David, being under the penalties for perjury state that this testimonial is true and reflects my personal experience.

In the Ghetto

I was born in Pesterzsébet, (now a district in Budapest) in 1921. We, my parents, 5 brothers and 4 sisters, lived in Nagyszőlős (Nagyszamolos?) Utca 170.

The Germans entered with full force into Hungary on the 19th of March 1944. Shortly after, they established the Ghettos in the city. They closed a two-streets block within our town with wooden fences and we had to move to that Ghetto. The Christian residents of these small and dilapidated flats had to leave, so we could go in.

I vividly remember that towards the end of May, the police sieged the Ghetto, guarding it around the clock. I befriended a young officer that expressed to me his regret about our fate. He said that youngsters like me would be taken away to Auschwitz to be exterminated and cremated. Those were his exact words. He added that he escorted Jews all the way to the trains that took them to Auschwitz. My older parents and the rest of my family didn’t believe any of what I told them.

Out of the Ghetto, into slavery in a factory

One morning, people from factories that worked for the Germans came to pick up their workers. After hearing what the police officer told me, I decided to do something. I sneaked into the line of workers that marched down the street without even knowing where they were headed to. I didn’t care where I was going, as long as it was out of the Ghetto. My sister Shari and my younger, 15 years old, brother Felix joined me. Felix actually ran away from the marching line right after we left the Ghetto and disappeared. Shari and I continued marching on.

We arrived to a textile factory owned by Mr. Ler that made uniforms for the Germans. It was a two-story building with lots of machines. Many worked there, came and went as they finished their workday. Shari and I, along with some 30 Jewish women, actually lived on the premises.

We worked 12 hour shifts from 6 am to 6 pm or 6 pm to 6 am. We slept in the attic. The floor was covered with hay, with wood planks that separated the space at a width of a bed, to form the sleeping berth of each of us. We got some food from the factory people as a wage. Each of us, in her turn, would cook some soup for our main meal. Each of us came with her plate to get a serving of whatever was prepared that day. Sometimes we had noodles or some kind of stew for dinner, which was the only one daily “real” meal. For breakfast we got coffee with a slice of bread, and for supper some dried food, a little white cheese, or some jam or something.

When we left the Ghetto, we only had the clothes we wore on us, nothing else. Several days later, around June the 2nd, they escorted us back to the Ghetto to pick up some additional clothes. By then the Ghetto was already empty of Jews. My parents and the rest of my siblings were gone. Gentiles that I knew told me how they saw the Gendarmes taking my parents with all the Jews away.

We got back to the factory with some blankets and clothes and continued working and living there. The factory was surrounded by a brick wall with an Iron Gate that was always closed and guarded. Obviously, we couldn’t leave the premises. Around mid-September we started hearing rumors that the Germans are taking the Jews out of these places as well.

From the Factory into Hiding.

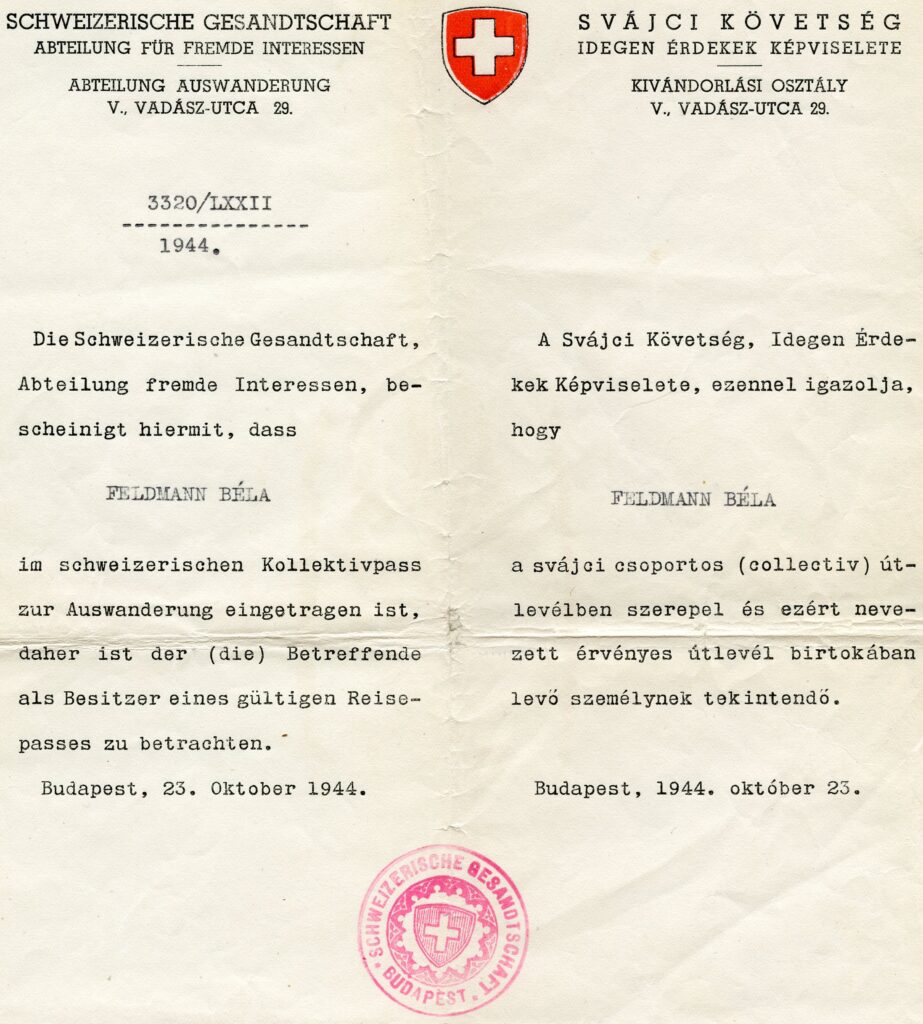

Bela Kovacs, a young Christian acquaintance we had, visited us frequently at our home before the war. He continued visiting us every now and then at the factory. We shared with him our plan to escape and asked for his help. Towards the mid-October, Bela succeeded in acquiring for us both Swiss Schutz-Brief – a Swiss Consulate issued certificate.

Consul Charles Lutz signed those Schutz-Briefs, a document that enabled its holders to move to Védett ház – Safe Houses. The Consul procured those houses in some miraculous way and declared them as a Swiss Territory. Bela took us out of the factory using these passes.

However, he didn’t take us to one of those safe houses. He explained that he saw the Nyilash (the Hungarian fascist youth movement) dragging out Jews from these safe houses. They dragged them to the bank of the Danube and shot them, dropping their corpses into the river.

Instead, he took us to a basement in a building on Angyal Utca 15. It was a small one room basement which he prepared for us as a hiding place. It had running water, a toilet and a small bathtub. Bela commanded us not to use the electricity there for fear that our presence would be revealed. He locked us inside the basement from the outside with a padlock; we couldn’t go out at all. It was in our protection. No one could come in without the proper keys. He believed that with all these measures could live there in relative safety.

Living in hiding

We were there in complete silence. Rather than talking we just occasionally whispered to each other. We dared not walking, but rather crawled if one of us had to move around. Almost all the time, day and night, awake or asleep, we laid under blankets; at least we were warm. We had not any warm drink for the whole 3 months until the liberation. Even if we had anything to heat things with, we were afraid to reveal our presence there by doing so. We were concerned not only for ourselves, but for Bela as well. It was well known that anyone, Christian or not, was executed for helping Jews.

Bela came approximately once a week, bringing us some bread, dried and canned food. We ate very conservatively, since we never knew when he could come again and bring us more food.

The siege on Budapest started around the 19th of December. We could tell that by the sound of the rapid shelling and gun fire that was coming closer. It was obvious to us that Bela will not come any more, until the fighting is over. It was a period of approximately a month. We ate sparingly from little bit of the dried bread and the few cans of food that we had left. Shortly after we filled up the small bathtub the water supply stopped. We used the water in the bathtub very conservatively, mainly to drink and minimally to wash ourselves.

Budapest was liberated by the Soviets on the 18th of January 1945. It took another day until it was safe to move around. Then Bela came, opened the locks and we were free.

After the War

Shortly after the liberation we went back home to look for our family. We found no one. Shari and I got into an apartment on Teréz körút 6; later our brother, Edgar (Ede) joined us. He survived the war in a Musz (abbreviation of the term “labor service man” in Hungarian). After the liberation, I suffered many illnesses: Gastrointestinal issues, rheumatism, depression and nervous breakdowns. It was so bad that I had to hospitalize myself into Szent Jảnos Hospital’s psychiatric ward, were I stayed for over then two weeks in 1946. Our brother, Felix, managed somehow to immigrate to Palestine and fought in Israel’s Independence War.

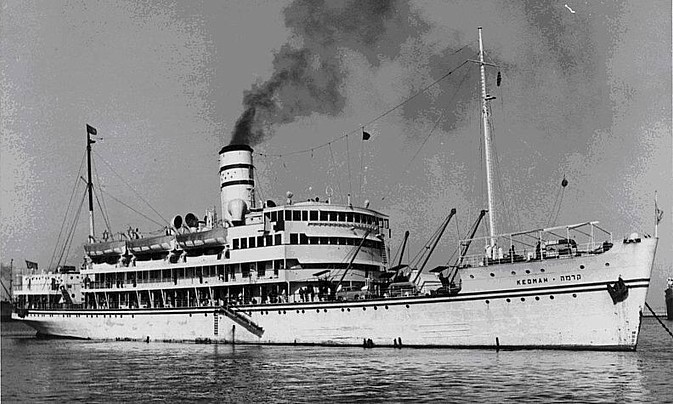

In 1949, after the establishment of Israel and the armistice agreement Ede, his wife Zsuzsi and I left illegally Hungary. We smuggled borders to Italy, where we boarded the Kedma (the name means Forward, Towards East) and immigrated to Israel.

I verify with my signature that everything that is recorded in this testimonial is the absolute truth and nothing but the truth.

Epilog – a Very Short One

I read, and reread the story. Emotions continue to float in full intensity. The questions that I have in my mind to answer, may surface in your minds too, after reading the story. You may even have answers for these questions. Maybe you would want to share your questions, answers, or both.

I feel that we all need time to let the story sit and penetrate, before continuing. It is almost too much to digest. Rather than sharing now my doubts, insights, regrets and forgiveness, I would like to invite you, to chime in. Let us, together, put it all in a follow-up article.