Introduction

This article adds to a previous one I posted about the meaning of prayers, with focus on the High Holidays. Some of you, my friends, asked me how prayers affected the healing miracle I experienced. Others questioned the effect of prayers altogether. It took me quite an effort to find words and explanations that express what I felt so deeply. I hope that my thoughts and experience will inspire some of you; I do invite your response and questions.

My friend Rabbi David Zaslow thought about the similarity between the lamp we light during Hanukkah and the human being. The lamp, or candle, have two components: the oil and the wick. Neither of them is an end in itself, and both are needed to support the flame that emits the light. The Hebrew word for “The Oil” is הַשֶׁמֶן – Hashemen. The very same Hebrew letters also make up the word נְשָׁמָה – Neshama, which means soul. A wick in Hebrew is פְּתִילָה – P’tilah. Rearranging the letters of this word creates the Hebrew word for Prayer – תְפִילָה – T’filah. Rabbi David says: “Prayer arises from the soul the same way oil arises through the wick to keep renewing the flame”.

He adds: “Prayer in Judaism is not an end in itself. Not any more than the oil is the goal of the candle. When we pray, we draw the oil from our physical existence, and it rises through the wick of our bodies. The enlightenment we feel is similar to the flame of the lamp. It’s the transformation of our life force into a light that reaches upward and outward from ourselves toward each other.” Whenever we light a candle, be it for Shabbat, Hanukkah or other festive occasions, this light becomes a nonverbal prayer. “Prayer is a means to an end,” continues Rabbi David, “an end that is our connection to the Divine.”

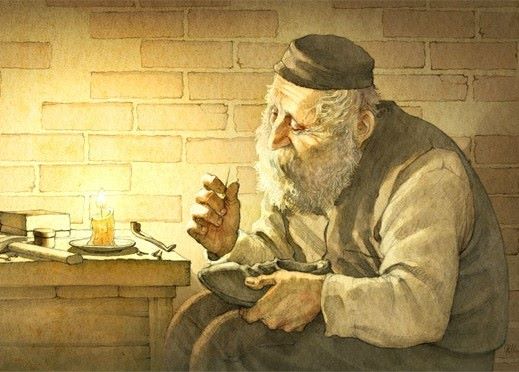

A Ḥasidic story adds color to Rabbi David’s teaching. It relates to a real-life encounter of Rabbi Israel Salanter, the founder of the Mussar Movement. It was late night when Rabbi Israel went to the synagogue to recite Seliḥot

(supplication service before the High Holidays). Suddenly he felt a tear in his shoe. He looked around town for a shoemaker that was still open for business at that late hour. Finally, he found a shoemaker sitting in his shop, working to the light of his candle. Rabbi Israel Lipkin walked in and asked: “Is it too late now to get my shoes repaired?” The shoemaker replied, “As long as the candle is burning, it is still possible to repair.”

Rabbi Israel hurried to the synagogue and preached to the public the lesson he had learned from the shoemaker. As long as the candle is burning – as long as one’s Neshama, soul, is still within the body – it is still possible to repair. Repair one’s own soul (through prayer and repentance), repair others with good deeds, repair the world (Tikkun Olam).

Rabbi David’s and Rabbi Israel’s teaching adds another layer to the verse in Proverbs 20:27:

Ner Adonai Nishmat Adam

נֵר יי נִשְׁמַת אָדָם

A traditional translation (Sefaria) is: The lifebreath of man is the lamp of the LORD. It also can mean: ‘The light of God shines within every human being and illuminates one’s soul’. And it can also mean the seemingly opposite direction, that connects to Rabbi David’s teaching. ‘The soul of Adam, every human being, IS a beacon that guides God’s Ways’. This interpretation really points in the direction of the subject matter in this article. The light of a person, the amalgam of one’s soul and prayer, IS a beacon that guides God’s ways.

Scientific Evidence

How Scientific Trials Are Conducted

Scientific tests are carried out in tightly controlled conditions, and medical tests are no exception. Medical tests, be it for new medicine, a procedure or a treatment, expose a group of subjects to the test. Sometime the subjects of the group may be animals, or human beings. The scientists try ensure that each individual participating in the test is very similar to the others within the group. The purpose of this effort is to minimize the number of variables that can affect the outcome of the test. The group of participants is then divided into two subgroups. One subgroup will receive the treatment that is the subject of the test. The other subgroup will receive the standard treatment or no treatment at all (placebo).

The most reliable test is the Double-Blind Trial. In a Double Blind, trial, the assignment of the individuals to each subgroup is random. Not a single participant in the trial knows the subgroup one belongs to. Furthermore: neither the medical team that treats the patients know that. All these measures try to minimize bias and irrelevant factors that might affect the outcome of the trial. I hope that this explanation might help some in better understanding the reports that quantify prayers’ efficacy on healing.

The answer to the question “Do prayers help?” is not a clear-cut absolute yes or no. Measuring the effect of prayers is intrinsically problematic, as it may involve nontangible results, that are not measurable. Designing a scientific trial that will measure that effect is a challenge in and by itself. I read quite a few articles in an effort to find a clear answer, and have selected to quote two. The first is “Prayer and healing: A medical and scientific perspective on randomized controlled trials”.

Highlights of The Abovementioned Article

This article explains first the mechanisms of healing through prayer. One of them is meditation, which results in psychological and biological changes in the body. These changes, in turn, improve the patient’s ability to cope with pain, decrease anxiety and instill positive mood. Another mechanism relates prayer to placebo effect that is tightly related to faith. One who receives a placebo pill and yet believes that he is taking the real medicine, might show temporary improvement. So is with prayer: one may believe that is prayer is answered positively, and shows, as a result, improvement. Prayer may also invoke health benefits and improvements due to Divine Intervention.

The article continues with some examples of the effect of the last mechanism – Divine Intervention. It lists two systematic reviews of many trials, both show that majority of studies indicated the positive effect of prayer on medical outcomes. On the other hand, the article also points out the methodological limitations and other difficulties associated with reviewing these studies. A common thread in most of these trials is the lack of personal and intimate acquaintance between the patient and ones who prays for healing. This might be a requirement that keeps the trial random and scientific.

Yet, one specific trial that is mentioned in this article is worthwhile elaborating on. It is a study on the effect of intercessory prayer on wound healing in a nonhuman primate species. 22 bushbabies with self-inflicted wounds were split into a prayer group and a control (placebo) group. Both groups received the same medical treatment; the “Prayer Group” was prayed for over a period of 4 weeks. Prayer group had a greater reduction of the wound size and better hematological parameters than those in the control group. The importance of this trial that being conducted on nonhuman subjects it lacked the effect of placebo.

Conclusion

The second article, from The Medical Journal of Australia, Prayer as Medicine, provides the conclusion of this section. The article talks about forms of prayer and its prevalence, and the plausible mechanisms in which prayers deliver health benefits. It also touched the issue of bias in researches about the effects of prayers.

“Throughout history, people have used prayer in relation to their own health and the health of others. While prayer continues to be a prevalent practice, scientific research on the health benefits of prayer is still in its infancy. To gain a clearer understanding of why people derive health benefits from prayer, future studies need to identify the unique markers that differentiate prayer from other non-spiritual practices. Researchers must also accept that some aspects of prayer may not be transparent to scientific investigation and may go beyond the reach of science. In the clinical context, prayer should not be specifically prescribed or seen as a substitute for medical treatment, but should be recognized as an important resource for coping with pain and illness and improving health and general wellbeing.”

Jewish Thought About Prayers for Healing

In this section, that relies on the work of Ariel Naftali, we’ll explore three elements. The first is the prayer of oneself for one’s own healing. The second would be the prayer of an individual (or community) for the healing of someone else. And the third is the prayer for healing by and for a non-Jew.

The Person Prays for One’s Own Healing

Is it permissible? Maybe not… Let’s assume that we believe that the mere appearance of the illness is the Will of God. In our prayer for our own healing, we defy that Will by asking God to change His Will. Another argument is that our prayer emerges from an egocentric intent and not from the pure love of God.

Rabbi Joseph Albo (1380-1333) in his work “The Book of Principles” offered a resolution to the first dilemma. “In Deuteronomy 30:20 we read: “thereby you shall have life and shall long endure”. From this verse it is clear that divine decrees are conditional upon the recipient’s certain state and degree of preparation. And if that changes, the decree changes also. This is the reason why the Rabbis say that a change of name may avail to nullify a decree. And similarly, the change of conduct may also change the decree.” According to his opinion, the prayer of the individual changes one’s spiritual condition. It may add humility, regret, confession and repentance to the person’s state of mind and behavior. That change in spirit impacts also the physical state and results with better abilities to cope with the disease.

The first to pray for his own healing is Ishmael (Genesis 21:17): “God heard the voice [cry] of the boy”. Rashi comments on this verse, saying: “From this we may infer that the prayer of a sick person is more effective than the prayer offered by others for him and that it is more readily accepted”. His prooftext is in Midrash Genesis Rabbah (53:14) which also supports Rabbi Albo’s assertion I mentioned earlier. The Midrash tells that just before God provided Hagar the well to draw water from for Ishmael, the angels protested. They told Him: “Master of the universe, this person will kill your sons in thirst, and you provide a well for him?” HaShem asked them in response: “Now, what is he: righteous or wicked?”. “Righteous”, they answered. The Omnipresent decreed: “I am not judging a person according to the future, but only at one’s present state”.

The Maimonides (Rambam) in his Mishneh Torah (a codex of 14 books on Jewish Law) rules that one should recite the following prayer prior to entering a medical treatment. “May it be Your will, God, our Lord, that this activity will bring me a recovery, for You are a generous healer.” And upon exiting the treatment, one should express gratitude for the healing: “Blessed are You, God… Healer of the sick.”

The Person Prays for Someone Else Healing

A famous biblical incidence for this form of prayer is when Moshe prayed for the healing of Miriam his sister. “Moshe cried out to HaShem, saying, ‘O God, I pray, please heal her!’” (Numbers 12:13). Talmud (B’rakhot 34a:13) deducts that the person who prays for one’s healing doesn’t need to mention one’s name. the thought and intent are adequate.

The Talmud (B’rakhot 5b) also talks about Rabbi Yoḥanan, that was known to have the power of healing. Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Abba, fell ill. Rabbi Yoḥanan entered to visit him, and said to him: …. Give me your hand. Rabbi Ḥiyya bar Abba gave him his hand, and Rabbi Yoḥanan stood him up and restored him to health. It continues in telling us that Rabbi Yoḥanan himself became ill. Rabbi Ḥanina entered to visit him, and said to him: …. Give me your hand. He gave him his hand, and Rabbi Ḥanina stood him up and restored him to health.

The Gemara asks: Why did Rabbi Yoḥanan wait for Rabbi Ḥanina to restore him to health? Afterall, he healed Rabbi Ḥiyya, so he could heal himself. The Gemara concludes that “A prisoner cannot free himself from prison, but depends on others to release him”. So is a sick person – one needs the help of others to heal.

The Maimonides (Mishneh Torah, Prayers 6:2-3) allows to deviate from the prescribed Amidah Prayer text for that purpose. “One may add in each of the middle blessings something relevant to that blessing if one desires. …If one desires to pray for healing of a sick person, one should request mercy in the blessing for the sick as eloquently as one can.”

The Talmud (Bava Kamma 92a) teaches us to pray for someone else even if we also need Heaven’s compassion. Because, in such a situation, our own needs will be answered first. Rava explains that by relating to the story of Avraham and Avimelekh (Genesis 20). Avraham and Sarah declare that they are siblings upon entering G’rar, the kingdom of Avimelekh. Avimelekh takes Sarah to be his wife; HaShem turns Avimelekh’s women barren as a punishment.

Avraham prays for Avimelekh (ibid 20:17). “Abraham prayed to God, and God healed Avimelekh and his wife and slave girls, so that they bore children.” Rava takes his clue from verse 21:1: “The LORD came to Sarah as he had said”. He claims that the words ‘he had said’ refer to the prayer of Avraham on behalf of Avimelekh. Avraham and Sarah were barren, and needed Heaven’s compassion, and yet, Avraham didn’t pray for himself, but for Avimelekh. Heaven’s compassion that healed Avimelekh’s wives also healed Avraham and Sarah.

The reason for this is, sages explain, the pure intentions of the praying person. The intent of the praying person is not for one’s own benefit, but to bestow good on someone else. The prayer is not for the sake of self-benefit, but expresses the recognition in the goodness of the Omnipresent. The merit of such a prayer is higher than a prayer that has a hint of self-benefit.

Prayer for Healing by and for a non-Jew

Jews must treat non-Jews in a similar way that they treat their own brethren. The Mishnah prohibits Jews to protest against poor non-Jews who take gleanings and produce left for to the Jewish poor. The Talmud (Gittin 61a:5) sages extend this directive even further, to foster peaceful relations between Jews and non-Jews. According to Talmud, Jews need to visit sick non-Jews along with sick Jews, and bury dead non-Jews along with Jews. Later responsa answer the question: can a Jew pray for the healing of a non-Jew? Say Kaddish on the non-Jew? The common answer is yes to both. The reasoning and substantiation are rather complex and way beyond the scope of this article.

A conversation between Rabbi Meir and his wife, Berurya (B’rakhot 10a) illuminates the Talmudic spirit about how to treat non-Jews. There were these hooligans in Rabbi Meir’s neighborhood who caused him a great deal of anguish. Rabbi Meir prayed for their demise. Rabbi Meir’s wife, Berurya, aske him: “On what basis do you pray for the death of these hooligans?” “Do you base yourself on the verse (Psalms 104:35): ‘Let sins cease from the land’?” She continued reprimanding him: “you interpret it to mean that the world would be better if the wicked were destroyed. Is it written, ‘let sinners cease?’ No, it says ‘Let sins cease’. One should pray for an end to their transgressions, not for the demise of the transgressors themselves.”

Can a Jew accept the prayer for healing of a non-Jew? the answer is yes. It leans on the Talmud (B’rakhot 51:b) that allows answering Amen after the blessing of the non-Jew Samaritan. From it one can deduct that a non-Jew (Samaritan) can make a blessing and participate in Jewish rituals. The Jerusalem Talmud (B’rakhot 8:8:7) goes even further. “It is stated: One answers Amen after a Gentile who recited a benediction for the Eternal. Rabbi Tanḥuma said, if a Gentile blesses you, answer after him Amen. As it is written in Deuteronomy 7:14: ‘You shall be blessed by all peoples.’”

Personal Reflections on Prayers for Healing

In my youth, I went with Dad to the local orthodox shul (there weren’t any other denominations in Israel then). There was no communal list of people in need of healing prayer (MiSeberakh list). Instead, anyone who needed to pray for healing of one’s relative would approach the Gabbai and ask for an Aliyah to the Torah. After the Aliyah and the blessing over the reading of Torah, Gabbai recited the Mi Sheberach for the sick prayer. The language is very specific: “He who blessed our fathers, Avraham, Itzḥak and Ya’akov, Moshe and Aharon, David and Shlomo, will bless the sick person (name) the son of (mother’s name) because (donor’s first name) son of (donor’s father’s name) pledged charity (amount donated), without a vow, for his/her sake. It is Shabbat when it is forbidden to plead; healing will come soon; and let us say, Amen.”

Then, the Gabbai would attach with a paperclip the sum of the donation (usually multiple of 18 – Ḥay, life) to the person’s index card. It follows the common saying “put your money where your mouth is”. Whenever one does a Mitzvah, there is a reward associated with it. The reward may be good feeling associated with the deed itself, and sometimes may be that one’s prayer is answered.

I personally prescribe to the orthodox inclination that I experienced in my youth. Rather than praying for myself, I pray for the healing of others. And in a completely separate time and intent, I pray gratitude to HaShem for the good He gives me. In my conversation with Passion I believe that I have already alluded to this approach. I responded that I draw strength and optimism, faith and hope, from my interaction with others that need support. Also, in the same conversation I shared my deep knowledge that whatever will be, it will be for good. And that is what I am grateful for.

My recent recovery from cancer is a miracle. Initial diagnosis indicated that the tumor in the liver was not operable, and a systemic therapy was the only option. During our research for the way to proceed, the community mobilized to hold a healing service and prayers for me. After only two therapy sessions of the eight the tumor showed regression so operation became a feasible option. Many friends and family continued praying and sending us letters of encouragement and positive energies. The surgeon directed to continue with two more cycles of therapy and then cease for 6 weeks. Following these additional sessions the tumor shrunk, but still was there. More blessings from friends followed, to which I responded with more gratitude. I had the privilege to lead Rosh Hashanah service with my community in Ashland. Then, I enjoyed immensely Yom Kippur services with my friends and family in Israel.

The surgeon was amazed not to find any sign of a tumor in the liver during the operation. Yet, he decided to remove the suspicious area and have the pathologists inspect it. No sigh for cancer was found. No one could explain this. There is very little experience with the success rate of the systemic therapy I received. None to speak of regarding the outcomes of doing only half the numbers of sessions. And none for the complete disappearance of the tumor altogether.

My extraordinary response to the treatment was, so I believe, thanks to the prayers of others. The prayers, the energy, the positive thoughts, strengthened me, and blew spirit of optimism and hope in me. That spirit was then amplified by the feelings of gratitude I have to HaShem, my family and friends. The tumor I had could not prevail such strong forces.

Judith graciously gave me the permission to share this personal story about the effect of prayers for healing. A single case may not prove that prayers always work; it shows that healing prayers did, at least once.

My mom was hospitalized unconscious and on a ventilator for two weeks. At that time, I worked at the Veterans Administration in White City Oregon. The non-Jewish Chaplain at the hospital asked me if it would be OK if he prayed for my mother. I assured him it was most welcome and very much appreciated.

Not only the Chaplain was praying for my mother. My brother sent prayers to the Kotel from Brooklyn. The Havurah Synagogue held a healing prayer circle for her in Ashland. And I did too.

I flew to NY to find my mom sitting up in bed. “Mom,” I said “what in the world is going on?”

She said, “I had a vision. A figure came to me and asked: Edith, do you want to come with me or stay?” I told him that I still enjoyed reading to the blind at the library and wanted to spend time with my grandchildren. This figure said to me: “I am very busy but I have heard prayers from Brooklyn, from Ashland Oregon and from Jerusalem. By the way….Where the heck is White City, Oregon? So…nu…. get up and go home already!!”

She left the hospital without any medication.

!מוֹדֶה אֲנִי לְפָנֶיךָ, מֶלֶךְ חַי וְקַיָּם, שֶׁהֶחֱזַרְתָּ בִּי נִשְׁמָתִי בְּחֶמְלָה. רַבָּה אֱמוּנָתֶךָ

I am so grateful and thank you, living and everlasting Sovereign, for returning back my soul in me with compassion. Great is your faith in me!