The Text Itself and Its Uniqueness

One of the key stories in Parashat Vayishlach is the meeting between the two brothers, Esav and Ya-akov. It starts at the very beginning of chapter 33. Here are verses 3-4:

He himself went on ahead of them [his wives and children] and bowed low to the ground seven times until he approached to his brother.

Esav ran towards him, embraced [hugged] him, falling on his neck, he kissed him; they wept.

וְה֖וּא עָבַ֣ר לִפְנֵיהֶ֑ם וַיִּשְׁתַּ֤חוּ אַ֙רְצָה֙ שֶׁ֣בַע פְּעָמִ֔ים עַד גִּשְׁתּ֖וֹ עַד אָחִֽיו׃

וַיָּ֨רׇץ עֵשָׂ֤ו לִקְרָאתוֹ֙ וַֽיְחַבְּקֵ֔הוּ וַיִּפֹּ֥ל עַל צַוָּארָ֖ו וַׄיִּׄשָּׁׄקֵ֑ׄהׄוּׄ וַיִּבְכּֽוּ׃

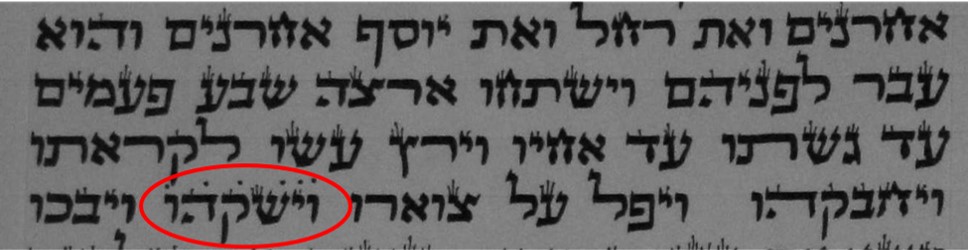

This is the way these two verses are written in the actual Torah Scroll:

The word that is encircled with an ellipse is וַׄיִּׄשָּׁׄקֵׄהׄוּׄ (vayishakehu) which means he kissed him. Please notice that this word is unique in that there are 6 dots, one above each letter of the word.

There are only 10 places in Torah that letters or words are dotted above the letters. Since there are no vowels or punctuations in Torah it draws attention and questions the reasons for these dots. A common explanation is that the transcript writers where not sure if the letter or word indeed was there in the original text.

What do the Dots Mean?

Playing What-Ifs with The Word

If we take out the word “Vayishakehu” (“he kissed him”) from the sentence, nothing is missing. Interestingly, in the Septuagint translation, the phrase ‘he kissed him’ is missing.

The fourth letter in the word is Kof (ק). What if it was khaf (כ) instead? The word וישׁכהו (VaYishakheu) means “he bit him”…

Take away the third letter, shin (שׁ): The word is וַיַקְהוּ – VaYak’hu – which means “they became dull, not sharp, blunted”. This verb may imply to any sharp object such as one’s teeth, or a knife…

Various Commentaries on the Meanings of the Dots

Rashi: HE KISSED HIM – the dots above this word trigger a difference of opinions in the Baraita of Sifré (בהעלותך). Some explain the dots mean that Esav did not kiss Ya‑akov with his whole heart. On the other hand, Rashbi said: we know very well that Esav hated Ya‑akov. But at that moment Esav’s pity really aroused and he kissed him with his whole heart. (Sifrei Bamidbar 69.2)

Radak sees significance in the fact that the word has a dot on each of its letters. He shows us two sides of the coin, relying on Bereshit Rabbah 78,9. Rabbi Shimon ben Elazar says that when there are less dots than letters in the word, we prefer the meaning of the text as is. When there are more dots than letters, we emphasize our interpretation to the dots. In this particular instance, there are as many dots as there are letters in the word. Thus, we understand that Esav kissed Ya‑akov sincerely with all his heart.

Rabbi Yannai countered Rabbi Shimon, asking: ‘if so, why bother putting any dots if they do not affect the meaning?’ He then interprets that originally Esav intended to bite Yaakov’s neck feigning an embrace. God made his teeth dull and soft as wax and Ya-akov’s neck as hard as ivory. They wept, one on account of his neck, the other on account of his teeth. Midrash Tanḥuma explains the same with a different parable, comparing it to a struggle between a wolf and a ram. The wolf bit the ram’s horns. He is crying for his teeth, and the ram is crying from fear that the wolf still may kill him.

Midrash Mishley 26:4: the dots on “kissed him” tell that the kiss was not out of love but from hate. Rabbi Shim’on Ben Menassi’a said: ‘Wicked Esav at that moment talked niceties on his lips, with hatred in his heart.’ He supported his assertion with appropriate proof texts from Proverbs and elsewhere.

Rabbi Shim’on Refa’el Hirsch presented an opposite view. The word “and they wept [cried]” is a trustworthy witness to the emergence of a pure humane feeing. Indeed, one can kiss without having his heart and soul into it. However, the tears that burst at that very moment strongly testify that they come from the bottom of the heart.

They reveal to us that Esav is also a descendent of Our Father Avraham, and not a mere savage hunter. How else could he reach the level of a leader in the human evolution? The swords itself, the mere physical power, are not adequate to prepare the person to lead and rule others. Esav slowly puts away his sword and gains in his heart the spirit of loving the other humans. Ya-akov, being the weak in this situation gives Esav the opportunity to prove that he is human. When Esav falls on the neck of Ya-akov and lets down his sword, he proofs that righteousness, humanity and loving kindness have the upper hand.

Rabbi Naftali Zvi Berlin (the Netziv) comments on this word in a similar way to R. Hirsch. He emphasizes that “They cried” – both of them cried. ‘That teaches us that the love to Esav arose in Ya-akov at that moment just as it was with Esav. That is how it needs to be for generations to come. Whenever the decedents of Esav awaken to acknowledge and respect our virtues, we need to acknowledge our brother, Esav. An example to this is Rabbi Yehuda HaNasi that really loved Caesar Antonius Pius, and it is one of many’.

Ibn Ezra also thinks positively and prefers to puts the weight on the simplistic interpretation the “Pshat”. Esav did not want to harm his brother, as it says that they both cried. He compared it to Yoseph’s reaction to his brothers, when they came to see him in Egypt (Genesis 45:1-2).

Ba’al Haturim calculated the numerical value of VAYISHAKEHU [kissed him] (427) and found it was equal to “LENOSHKHEHU [bit him]. In addition, to support that notion, he said that the numerical value of Esav (366) equals to SHINAV – his teeth…

Zooming Out to See the Overall Scene

In a separate teaching on this Parasha I suggested that maybe the angel Ya-akov struggled with was actually God Himself. Midrash (B’reshit [77] and Shir Hashirim Rabba and others) suggest a different option: it was Esav’s Ministering Angel. The angel could not defeat Ya-akov, and had to bless him so he could leave to his morning duties. That lessened Esav’s anger, became open to accept Ya-akov’s offerings and did not harm him as he initially planned to. Midrash uses verse 33:10 as a hook to this angle:

Ya-akov said, “No, please; if you would do me this favor, accept from me this gift; for I [previously] saw your face like seeing the face of God, and [then] you received me favorably.”

וַיֹּ֣אמֶר יַעֲקֹ֗ב אַל־נָא֙ אִם־נָ֨א מָצָ֤אתִי חֵן֙ בְּעֵינֶ֔יךָ וְלָקַחְתָּ֥ מִנְחָתִ֖י מִיָּדִ֑י כִּ֣י עַל־כֵּ֞ן רָאִ֣יתִי פָנֶ֗יךָ כִּרְאֹ֛ת פְּנֵ֥י אֱלֹהִ֖ים וַתִּרְצֵֽנִי׃

The Midrash explains that Ya-akov tells that he met Esav’s ministering angel and struggled with him. At the end of the encounter the Ministering angel was favorable to him and blessed him. So there is no reason to continue fighting. In that sentence, Ya-akov shows respect and honors Esav, by being humble and lowly. And it also shows strength and recognition in his own stance with God: ‘You, Esav’s Ministering Angel, saw that God stands next to me; therefore, despite your strength you could not defeat me’.

A Look at Another, Well-Connected, Snippet in the Parasha.

Almost as an anecdotal story in the Parasha and over only 3 verses (ibid 35:27-29) we read about Yitzḥak’s death. Ya-akov came to visit his 180 years old father in Ḥevron, and then (35:29):

Yitzḥak breathed his last, died and was gathered to his kin in ripe old age; his sons Esav and Ya-akov buried him.

וַיִּגְוַ֨ע יִצְחָ֤ק וַיָּ֙מָת֙ וַיֵּאָ֣סֶף אֶל־עַמָּ֔יו זָקֵ֖ן וּשְׂבַ֣ע יָמִ֑ים וַיִּקְבְּר֣וּ אֹת֔וֹ עֵשָׂ֥ו וְיַעֲקֹ֖ב בָּנָֽיו׃

In my teaching about Parashat Ḥayey Sarah, I referred to the same episode that happed with their grandfather Avraham. We read in Genesis 25:9:

And Avraham breathed his last, dying at a good ripe age, old and contented and was gathered to his kin. His sons Yitzḥak and Ishmael buried him in the cave of Makhpelah.

וַיִּגְוַ֨ע וַיָּ֧מׇת אַבְרָהָ֛ם בְּשֵׂיבָ֥ה טוֹבָ֖ה זָקֵ֣ן וְשָׂבֵ֑עַ וַיֵּאָ֖סֶף אֶל־עַמָּֽיו׃ וַיִּקְבְּר֨וּ אֹת֜וֹ יִצְחָ֤ק וְיִשְׁמָעֵאל֙ בָּנָ֔יו אֶל־מְעָרַ֖ת הַמַּכְפֵּלָ֑ה

Yet there is a small difference, in the order the Torah calls out the sons that bury their father. In the former event, Yitzḥak is mentioned first, before Ishmael, even though he was the younger. The reason for that is that they were only half-brothers and Yitzḥak had the higher priority, or status. In the funeral of Yitzḥak, however, both siblings are equal in their status; and Esav is the firstborn. The fact that Esav foregone the rite to Ya-akov doesn’t count. At the funeral, the moment of Ḥesed Shel Emet – the ultimate act of lovingkindness, Esav is mentioned first.

Takeaways to Today’s Life

I Ḥayey Sarah essay I alluded to the belief of Muslims that Muhammed relates Ishmael and said there:

“We, Muslims and Jews alike, especially those who live in Eretz Israel, need to learn this lesson from our ancestors. Ishma’el and Yitzḥak, two siblings, offspring of Avraham overcame their differences. When it came to the moment of absolute truth, they did together the Ḥesed Shel Emet and buried their father. It is so important for all of us to remember that both our ancestors buried together our common forefather, putting aside all the “rational” reasons not to do so.”

In a similar way, many Jewish sources (Midrash Esther Rabba, Zohar) and commentators connect Esav to the Romans and Christianity. The same message regarding the relationship between Muslims and Jews, applies much more so to the Christian world. Itzḥak and Ishmael were half-brothers; Ya-akov and Esav were twins!

I would like to take the teaching of the Netziv, Rabbi Naftaly Zvi Berlin, a little further. He said: ‘Whenever the decedents of Esav awaken to acknowledge and respect our virtues, we need to acknowledge our brother, Esav’. I suggest that we do not need to wait for Esav’s decedents to acknowledge our virtues. Rather, we should initiate our acknowledgement of their virtues. After all, we know our values and qualities and feel confident about them.

We need to take the proactive step forward, and project the positive and the light within our Jewish values. Owning and respecting our own identities and values will draw the respect of others. Our interactions with the non-Jewish neighbors need to come with love. Because we hold dear the commandment to “love to your fellow human being as yourself, I am Adonai”. May we all cherish the common values and teachings we share and at the same time respect our differences.